After the 1968 election, Rather asked to stay in Washington to cover the Nixon administration. He welcomed the changes and looked forward to getting to know the new men in the White House and work with the new press secretary Ron Ziegler. Unlike other presidents, however, Nixon was guarded from the very beginning and had White House Chief of Staff Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, the counsel and assistant to the president for domestic affairs, running interference for him. The Nixon administration wanted to establish a kind of authority over the television networks. The philosophy was that, to be fair, coverage had to be favorable.

The Nixon men went through a fairly long, carefully orchestrated campaign to disrupt and discredit the press. They tried to sow rivalry and competition among correspondents, “to wedge” them. They also worked to intimidate news organizations or individuals, spying and placing illegal listening devices. Talking to Richard Salant, the president of CBS News, Ehrlichman suggested, for example, that Rather should be moved to Austin and, even better, be given a year’s vacation. When Rather confronted him, Ehrlichman, joined by Haldeman, told him that he was inaccurate and unfair, and that he was wrong 90 percent of the time.

As Rather recalls, Haldeman was antagonistic from the beginning, calling Rather “a Lyndon Johnson, Texas liberal Democrat” in January 1969. The White House wrote detailed internal memos about the network newscasters and commentators, categorizing them as “Generally for Us,” “Generally Objective,” and “Generally Against Us.” In June 1969, Rather was described a “more favorable than he was prior to the election. He is generally objective on television and sometimes negative on radio in his interpretative reporting.” In November 1969, he was in the category “Generally Objective.” In December 1969, aide to the White House Herbert H Klein wrote “I believe [Rather] is a Democrat but he generally covers the news fairly. He has had some complimentary things to say about us. . . . I guess I would say he is 'not bad.'” An undated memo decribes Rather as “tries to be objective, but in this effort tends to feel his obligation to point out negative rather than positive in a story. He check facts frequently, however.”

President Nixon sent Vice President Spiro T Agnew to declare what Newsweek called a “bitter, slashing attack.” At the Midwest Regional Republican Convention on November 13, 1969, in Des Moines, Iowa, Agnew specifically criticized “instant analysis and querulous criticism”—the commentaries journalists do, often off the cuff, after a speech, as well the power of editing. He attacked the “unelected elite,” this “small band of commentators and self appointed analysts,” the group of men who, in his opinion, decide and influence what millions of American are watching on television. Time magazine featured twelve men that stood out at the top of the profession, including anchors and journalist (David Brinkley and Chester Huntley, Walter Cronkite and Eric Severeid, Frank Reynolds and Howard K Smith), producers (Leslie Midgley, Wallace Westfeld, and Av Westin) and presidents of news (Reuven Frank from NBC, Elmer Lower from ABC ,and Richard Salant at CBS News). Agnew’s speech had far-reaching repercussions as it heralded the now common practice by political powers to attack the press, a kind of “working the refs,” in order to get political points.

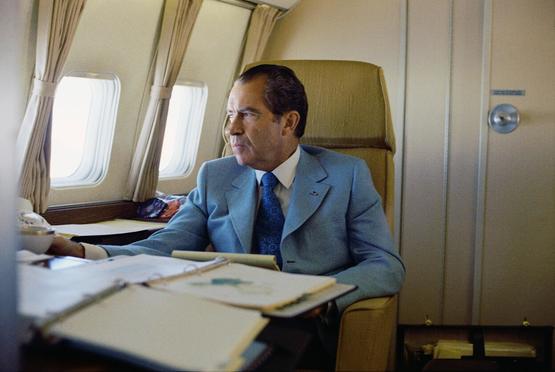

The relationship between the White House and the press deteriorated rapidly, and the space for the press shrank considerably under Nixon. He would even be the first president to bar pool reporters, even the wire services, from Air Force One on a regular basis. After the New York Times published the Pentagon Papers, Nixon ordered Haldeman in 1971 to see to it that ''under absolutely no circumstances is anyone on the White House staff, on any subject, to respond to an inquiry from the New York Times unless and until I give express permission—and I do not expect to give such permission in the foreseeable future.'' He asked for an “an all-out, slam-bang attack” on the press.

In response, the National Press Club asked the Department of Communications at the American University to conduct a study about the topic. A report in May 1973, concluded that a serious breakdown had occurred in communication between the federal government and the public. The study found evidence of “attempts by the administration to restrict the flow of legitimate public information necessary to the effective functioning of a democracy.” The Nixon administration had engaged “in a three-year- long concerted effort to discredit the press” and in an “unprecedented, government-wide effort to control, restrict and mange public information.” It used the courts to pursue a policy of harassment and intimidation of the press while seeking to manipulate content of public broadcasting for political purposes.